RESEARCH CONSIDERATIONS - You will need to review your existing research undertaken in response to the lectures, seminars and tasks from the first part of this module in order to identify specific areas of interest or points of focus. These could take the form of quotes, images, examples, critical responses, tasks, principles, ideas or concepts.

DEVELOPMENT CONSIDERATIONS - What do you want to say and how do you want to say it? How will you translate your research into content? What form or format will it take? Questions, answers, statements, quotes, images, photographs, drawings, diagrams etc. ? Can you combine these elements ? If so....How? How will you organise the content? How will you make it interesting?

RESOLUTION CONSIDERATIONS - What is a publication? How is it made? What format could it be? How is the format relevant to the content? Is this important? What are the conventions of publication? How do you work with these? What are the rules? Do you have to obey them?

From the first part of the module I have been most interested in Modernism so I want to use this as my main point of focus.

RESEARCH CONSIDERATIONS - You will need to review your existing research undertaken in response to the lectures, seminars and tasks from the first part of this module in order to identify specific areas of interest or points of focus. These could take the form of quotes, images, examples, critical responses, tasks, principles, ideas or concepts.

Content Research

MODERNISM

"Never before have the conditions of life changed so swiftly and enormously as they have… in the last fifty years. We have been carried along… [and] we are only now beginning to realize the force and strength of the storm of change that has come upon us."

H .G . WELLS, 1933

Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement in the arts, its set of cultural tendencies and associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In particular the development of modern industrial societies and the rapid growth of cities, followed then by the horror of World War I, were among the factors that shaped Modernism. Born of great cosmopolitan centres, it flourished in Germany and Holland, as well as in Moscow, Paris, Prague and New York.

During the interwar years of 1914 to 1939, many architects, designers, and artists passionately committed themselves to the ideas which we now call Modernism. Reacting to the unprecedented violence and destruction of World War I, they searched for ways to create a better world through art and design.

UTOPIA

"A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not even worth glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which humanity is always landing."

"A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not even worth glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which humanity is always landing."

OSCAR WILDE, 1891

Modernist artists and designers were frequently driven by a Utopian belief in the power of their creations. They believed artists and designers could apply new technology, combined with a single, all-embracing methodology, to every part of the manufactured environment—including buildings, furnishings, products, interiors, signage, posters, and clothing—to significantly improve people’s physical and psychological conditions. This passion, together with political transformations taking place throughout the world, gave the Modernists powerful motivation. They believed in a “total art”; the idea that all art should work in unison to transform the environment. How their work looked was just one of their concerns; what it meant and how it was used were equally important.

THE MACHINE

AND MASS PRODUCTION

No idea was more central to the creation of a new Utopia than that of technology, represented by images of “the machine.” The industrialization of the landscape and the prevalence of a machine aesthetic in the design and production of goods linked Modernists to workers and helped connect artists to the realities of everyday life. This notion inspired the multidisciplinary design and art program at the Bauhaus school in Germany. Bauhaus founder and architect Walter Gropius believed that the innate design of an industrial object, building, or home could directly affect community and city planning. Many important artists, designers, and architects contributed to the Bauhaus experiment through teaching, including László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer.

AND MASS PRODUCTION

"The new life of iron and the machine, the roar of automobiles, the glitter of electric lights, the whirring of propellers, have awoken the soul."

KAZIMIR MALEVICH , 1916

No idea was more central to the creation of a new Utopia than that of technology, represented by images of “the machine.” The industrialization of the landscape and the prevalence of a machine aesthetic in the design and production of goods linked Modernists to workers and helped connect artists to the realities of everyday life. This notion inspired the multidisciplinary design and art program at the Bauhaus school in Germany. Bauhaus founder and architect Walter Gropius believed that the innate design of an industrial object, building, or home could directly affect community and city planning. Many important artists, designers, and architects contributed to the Bauhaus experiment through teaching, including László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer.

THE BAUHAUS

1919-1933

Founded in Weimar in 1919, the Bauhaus rallied masters and students who sought to reverse the split between art and production by returning to the crafts as the foundation of all artistic activity and developing exemplary designs for objects and spaces that were to form part of a more human future society. Following intense internal debate, in 1923 the Bauhaus turned its attention to industry under its founder and first director Walter Gropius (1883–1969). The major exhibition which opened in 1923, reflecting the revised principle of art and technology as a new unity, spanned the full spectrum of Bauhaus work. The Haus Am Horn provided a glimpse of a residential building of the future.

1919-1933

The Bauhaus occupies a place of its own in the history of 20th century culture, architecture, design, art and new media. One of the first schools of design, it brought together a number of the most outstanding contemporary architects and artists and was not only an innovative training centre but also a place of production and a focus of international debate. At a time when industrial society was in the grip of a crisis, the Bauhaus stood almost alone in asking how the modernisation process could be mastered by means of design.

Founded in Weimar in 1919, the Bauhaus rallied masters and students who sought to reverse the split between art and production by returning to the crafts as the foundation of all artistic activity and developing exemplary designs for objects and spaces that were to form part of a more human future society. Following intense internal debate, in 1923 the Bauhaus turned its attention to industry under its founder and first director Walter Gropius (1883–1969). The major exhibition which opened in 1923, reflecting the revised principle of art and technology as a new unity, spanned the full spectrum of Bauhaus work. The Haus Am Horn provided a glimpse of a residential building of the future.

In 1924 funding for the Bauhaus was cut so drastically at the instigation of conservative forces that it had to seek a new home. The Bauhaus moved to Dessau at a time of rising economic fortunes, becoming the municipally funded School of Design. Almost all masters moved with it. Former students became junior masters in charge of the workshops. Famous works of art and architecture and influential designs were produced in Dessau in the years from 1926 to 1932.

Walter Gropius resigned as director on 1st April 1928 under the pressure of constant struggles for the Bauhaus survival. He was succeeded by the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer (1889–1954) whose work sought to shape a harmonious society. Cost-cutting industrial mass production was to make products affordable for the masses. Despite his successes, Hannes Meyer’s Marxist convictions became a problem for the city council amidst the political turbulence of Germany in 1929, and the following year he was removed from his post.

Under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) the Bauhaus developed from 1930 into a technical school of architecture with subsidiary art and workshop departments. After the Nazis became the biggest party in Dessau at the elections, the Bauhaus was forced to move in September 1932. It moved to Berlin but only lasted for a short time longer. The Bauhaus dissolved itself under pressure from the Nazis in 1933.

KEY ARTISTS:

link

Their probing for a means to reconcile the artist and the machine became the inspiration for the "Bauhaus," its purpose was to pursue new forms and new solutions to man's basic needs as well as his aesthetic ones. The Bauhaus' curriculum returned to fundamentals, the basic materials, the basic rules of design. And the question they dared to ask led to new definitions of beauty in the unadorned and practical aspects of the functional.

Functional Techniques:

- Simplicity

- Symmetry

- Angularity

- Abstraction

- Consistency

- Unity

- Organization

- Economy

- Subtlety

- Continuity

- Regularity

- Sharpness

- Monochomaticity

link

To allow Bauhaus designers to fabricate goods from basic units, they developed a clean, simple style using abstract, angular and geometric forms. These forms were inspired by modern machinery – wheels, pistons and other mechanical elements. This principle of applying industrial imagery to architecture and domestic design appeared severe in contrast to the curves and decoration of the Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts movements. Bauhaus’ austere aesthetic symbolised and dominated avant-garde architecture and design and its partnership with technology.

Bauhaus encouraged the use of new materials, including tubular steel, concrete, glass and plywood. Designers allowed the structure and construction of their finished designs to dictate their outward appearance – to such an extent that they regarded their designs as “styleless”. This followed on from American architect Louis Sullivan’s ideas on

form following function.

“It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic, of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human and all things superhuman, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function. This is the law.” Louis Sullivan, 1896

Interpreting “Form Follows Function”

There are two ways to interpret the phrase “form follows function”:

- Descriptive: beauty results from purity of function;

- Prescriptive: aesthetic considerations in design should be secondary to functional considerations.

DESCRIPTIVE INTERPRETATION

The descriptive interpretation favors simplicity to complexity. It states that beauty results from purity of function and not from ornamentation. This ideal derives from the belief that form follows function in nature. Is this really true?

Actually, the opposite is true. Evolution passes on genetic traits to subsequent generations without any rationale for their purpose. Each generation of a species then finds a use for the form it has inherited. Function follows form in nature.

Applying functional elements to a design is generally a more objective process than applying aesthetic elements. A functionally objective process results in designs that are timeless but may be perceived as simple and uninteresting.

PRESCRIPTIVE INTERPRETATION

The prescriptive interpretation prioritizes functionality over all other design considerations, including usability, ergonomics and aesthetics.

Aesthetic considerations in design should be secondary to functional considerations. Is this interpretation problematic? Does it lead designers to ask the wrong questions about a given design?

This interpretation would seem to lead to designers to ask what should be omitted from a design. What elements of a design do not serve a function and thus ought to be removed? Should the form of a design be determined solely by its function?

Taken to the logical conclusion, every element would ultimately have the same design. Every functional item would have one and only one design. Before an object’s form could be changed, it would need to serve a different function.

Better questions come from your criteria for success. What aspects of you design are critical to success? When time or resources is limited, what design trade-offs would least harm the design’s success? Sometimes, certain aesthetics will have to be abandoned, and sometimes certain functionality will have to be abandoned. Sometimes both aesthetics and functionality will need to be compromised.

Life and Career

Rams began studies in architecture and interior decoration at Wiesbaden School of Art in 1947. Soon after in 1948, he took a break from studying to gain practical experience and conclude his carpentry apprenticeship. He resumed studies at Wiesbaden School of Art in 1948 and graduated with honours in 1953 after which he began working for Frankfurt based architect Otto Apel. In 1955, he was recruited to Braun as an architect and an interior designer. In addition, in 1961, he became the Chief Design Officer at Braun until 1997.

Dieter Rams was strongly influenced by the presence of his grandfather, a carpenter. Rams once explained his design approach in the phrase "Weniger, aber besser" which translates as "Less, but better".

Rams and his staff designed many memorable products for Braun including the famous SK-4 record player and the high-quality 'D'-series (D45, D46) of 35 mm film slide projectors. He is also known for designing the 606 Universal Shelving System by Vitsœ in 1960.

By producing electronic gadgets that were remarkable in their austere aesthetic and user friendliness, Rams made Braun a household name in the 1950s. He is considered to be one of the most influential industrial designers of the 20th century.

Rams has been an outspoken voice calling for “an end to the era of wastefulness” and to consider how we can continue to live on a planet with finite resources if we simply throw everything away.

“I imagine our current situation will cause future generations to shudder at the thoughtlessness in the way in which we today fill our homes, our cities and our landscape with a chaos of assorted junk.”

He drew attention to an “increasing and irreversible shortage of natural resources”. Believing that good design can only come from an understanding of people, Rams asked designers – indeed, everyone – to take more responsibility for the state of the world around them.

Back in the late 1970s, Dieter Rams was becoming increasingly concerned by the state of the world around him – “an impenetrable confusion of forms, colours and noises.” Aware that he was a significant contributor to that world, he asked himself an important question: is my design good design?

As good design cannot be measured in a finite way he set about expressing the ten most important principles for what he considered was good design. Dieter Rams: ten principles for good design

1.

Good design is innovative TP 1 radio/phono combination, 1959, by Dieter Rams for Braun

TP 1 radio/phono combination, 1959, by Dieter Rams for Braun

The possibilities for progression are not, by any means, exhausted. Technological development is always offering new opportunities for original designs. But imaginative design always develops in tandem with improving technology, and can never be an end in itself.

2.

MPZ 21 multipress citrus juicer, 1972, by Dieter Rams and Jürgen Greubel for Braun

MPZ 21 multipress citrus juicer, 1972, by Dieter Rams and Jürgen Greubel for Braun

A product is bought to be used. It has to satisfy not only functional, but also psychological and aesthetic criteria. Good design emphasizes the usefulness of a product whilst disregarding anything that could detract from it.

3.

RT 20 tischsuper radio, 1961, by Dieter Rams for Braun

RT 20 tischsuper radio, 1961, by Dieter Rams for Braun

The aesthetic quality of a product is integral to its usefulness because products are used every day and have an effect on people and their well-being. Only well-executed objects can be beautiful.

4.

T 1000 world receiver, 1963, by Dieter Rams for Braun

T 1000 world receiver, 1963, by Dieter Rams for Braun

It clarifies the product’s structure. Better still, it can make the product clearly express its function by making use of the user's intuition. At best, it is self-explanatory.

5.

Cylindric T 2 lighter, 1968, by Dieter Rams for Braun

Cylindric T 2 lighter, 1968, by Dieter Rams for Braun

Products fulfilling a purpose are like tools. They are neither decorative objects nor works of art. Their design should therefore be both neutral and restrained, to leave room for the user's self-expression.

6.

L 450 flat loudspeaker, TG 60 reel-to-reel tape recorder and TS 45 control unit, 1962-64, by Dieter Rams for Braun

It does not make a product appear more innovative, powerful or valuable than it really is. It does not attempt to manipulate the consumer with promises that cannot be kept.

7.

620 Chair Programme, 1962, by Dieter Rams for Vitsœ

It avoids being fashionable and therefore never appears antiquated. Unlike fashionable design, it lasts many years – even in today's throwaway society.

ET 66 calculator, 1987, by Dietrich Lubs for Braun

ET 66 calculator, 1987, by Dietrich Lubs for Braun

Good design is environmentally-friendly

8.

Good design is thorough down to the last detail

ET 66 calculator, 1987, by Dietrich Lubs for Braun

ET 66 calculator, 1987, by Dietrich Lubs for Braun

Nothing must be arbitrary or left to chance. Care and accuracy in the design process show respect towards the consumer.

9.

606 Universal Shelving System, 1960, by Dieter Rams for Vitsœ

606 Universal Shelving System, 1960, by Dieter Rams for VitsœDesign makes an important contribution to the preservation of the environment. It conserves resources and minimizes physical and visual pollution throughout the lifecycle of the product.

10.Good design is as little design as possible

L 2 speaker, 1958, by Dieter Rams for Braun

Less, but better – because it concentrates on the essential aspects, and the products are not burdened with non-essentials. Back to purity, back to simplicity.

link

Braun

The starting point for the new design concept was a positive assessment of the potential shopper: intelligent and open-minded, someone who appreciated unobtrusive products which left him or her ample freedom for personal fulfilment.

After a landmark speech by designer Wilhelm Wagenfeld on industrial design and the responsibility of the entrepreneur, Erwin Braun felt so strongly confirmed in his plans that he immediately commissioned Wagenfeld with a design assignment. Seeking further designers, Braun in late 1954 discovered the fledgling

“Hochschule fuer Gestaltung” design academy in Ulm, which set out to carry on the work of the Bauhaus movement disbanded by the Nazis in 1933. With the two lecturers Hans Gugelot and Otl Aicher, a team had been created that was to go down in design history.

In only eight months, they succeeded in giving the entire Braun product line – from portable radios to music cabinets – a completely new face. The first major launch event was the 1955 Electronic Exhibition in Duesseldorf. The stand developed by Otl Aicher signalized even from afar that something fundamentally new was being offered there.

The hiring of 23-year-old Dieter Rams, likewise in 1955, had far-reaching implications. Rams started as an interior designer and soon became the nucleus of Braun’s own design department. Headed by Fritz Eichler, it commenced its work, with freelance help, in 1956. Gradually, the new design style spread not only to the entire product line, but also to all communications instruments – from stationery and use instructions all the way to advertising. This gave Braun a corporate identity long before the term was even coined.

The new design concept implemented by Dieter Rams and the Braun design team quickly gained fame; as early as in the late 1950’s, Braun products were selected for prestigious permanent collections such as at the MoMa in New York. During this period, Braun’s traditional strength in radios, record players and combined hi fi units continued. However, starting in the 1960’s, Braun electric shavers, led by the renowned sixtant, became a key business segment, as did household products such as kitchen machines and juicers, which were launched in the new design look in the late 1950’s and expanded to international markets in the 1960’s.

In the 1970’s and 80’s additional product segments became important and made new demands on the Braun design team. Hand-held hair dryers were developed in the 70’s, in the late 70’s also styling appliances. These personal care products required design that focused on ergonomics and ease of handing. Clocks, watches and calculators were important primarily in the 1980’s and set new design standards for clarity and reduction, combined with innovative technology. During the 1980’s Braun concluded its presence in the HiFi business with an exclusive ‘Limited edition’ to then focus on the more lucrative small appliance sector, in particular personal care and household products. Shavers became – and still are today - the biggest business segment for Braun, featuring design innovations such as two-component molding to achieve soft nubs on a hard housing, for better handling.

link

Apple

The year 2013 marks the 15th Anniversary of the iMac, the computer that changed everything at Apple, hailing a new design era spearheaded by design genius Jonathan Ive. What most people don't know is that there's another man whose products are at the heart of Ive's design philosophy, an influence that permeates every single product at Apple, from hardware to user-interface design. That man is Dieter Rams, and his old designs for Braun during the '50s and '60s hold all the clues not only for past and present Apple products, but their future as well:

Detail of the radio perforated aluminum surface.

Braun LE1 speaker and Apple iMac.

link

Braun

Founded:

1921 in Frankfurt am Main by Max BraunThe new design concept and start of era Dieter Rams

The starting point for the new design concept was a positive assessment of the potential shopper: intelligent and open-minded, someone who appreciated unobtrusive products which left him or her ample freedom for personal fulfilment.

After a landmark speech by designer Wilhelm Wagenfeld on industrial design and the responsibility of the entrepreneur, Erwin Braun felt so strongly confirmed in his plans that he immediately commissioned Wagenfeld with a design assignment. Seeking further designers, Braun in late 1954 discovered the fledgling

“Hochschule fuer Gestaltung” design academy in Ulm, which set out to carry on the work of the Bauhaus movement disbanded by the Nazis in 1933. With the two lecturers Hans Gugelot and Otl Aicher, a team had been created that was to go down in design history.

In only eight months, they succeeded in giving the entire Braun product line – from portable radios to music cabinets – a completely new face. The first major launch event was the 1955 Electronic Exhibition in Duesseldorf. The stand developed by Otl Aicher signalized even from afar that something fundamentally new was being offered there.

The hiring of 23-year-old Dieter Rams, likewise in 1955, had far-reaching implications. Rams started as an interior designer and soon became the nucleus of Braun’s own design department. Headed by Fritz Eichler, it commenced its work, with freelance help, in 1956. Gradually, the new design style spread not only to the entire product line, but also to all communications instruments – from stationery and use instructions all the way to advertising. This gave Braun a corporate identity long before the term was even coined.

The new design concept implemented by Dieter Rams and the Braun design team quickly gained fame; as early as in the late 1950’s, Braun products were selected for prestigious permanent collections such as at the MoMa in New York. During this period, Braun’s traditional strength in radios, record players and combined hi fi units continued. However, starting in the 1960’s, Braun electric shavers, led by the renowned sixtant, became a key business segment, as did household products such as kitchen machines and juicers, which were launched in the new design look in the late 1950’s and expanded to international markets in the 1960’s.

In the 1970’s and 80’s additional product segments became important and made new demands on the Braun design team. Hand-held hair dryers were developed in the 70’s, in the late 70’s also styling appliances. These personal care products required design that focused on ergonomics and ease of handing. Clocks, watches and calculators were important primarily in the 1980’s and set new design standards for clarity and reduction, combined with innovative technology. During the 1980’s Braun concluded its presence in the HiFi business with an exclusive ‘Limited edition’ to then focus on the more lucrative small appliance sector, in particular personal care and household products. Shavers became – and still are today - the biggest business segment for Braun, featuring design innovations such as two-component molding to achieve soft nubs on a hard housing, for better handling.

BraunCollection

The BraunCollection archive contains some 5,600 products spanning 90 years. Approximately 2,800 of these are one-off items that never went into series production.

link

Apple

Jonathan Ive

Jonathan Ive, officially the senior vice president of industrial design at Apple, and he has long acknowledged Dieter Rams as his inspiration.

Rams, who has never spoken at any length about Apple, was the man behind Braun when it made a host of classic gadgets from radios to juicers, and he’s the subject of a forthcoming celebration published by Phaidon, to which Ive has written the foreword.

When Ive talks about Rams designing “surfaces that were without apology, bold, pure, perfectly-proportioned, coherent and effortless”, he could equally be talking about the iPod. “No part appeared to be either hidden or celebrated, just perfectly considered and completely appropriate in the hierarchy of the product’s details and features. At a glance, you knew exactly what it was and exactly how to use it.”

Ive goes on to say that “what Dieter Rams and his team at Braun did was to produce hundreds of wonderfully conceived and designed objects: products that were beautifully made in high volumes and that were broadly accessible”. Little wonder, then, that the calculator on the iPhone and iPod Touch is so clearly inspired by Rams’ version for Braun.

The year 2013 marks the 15th Anniversary of the iMac, the computer that changed everything at Apple, hailing a new design era spearheaded by design genius Jonathan Ive. What most people don't know is that there's another man whose products are at the heart of Ive's design philosophy, an influence that permeates every single product at Apple, from hardware to user-interface design. That man is Dieter Rams, and his old designs for Braun during the '50s and '60s hold all the clues not only for past and present Apple products, but their future as well:

When you look at the Braun products by Dieter Rams—many of them at New York's MoMA—and compare them to Ive's work at Apple, you can clearly see the similarities in their philosophies way beyond the sparse use of color, the selection of materials and how the products are shaped around the function with no artificial design, keeping the design "honest."

This passion for "simplicity" and "honest design" that is always declared by Ive whenever he's interviewed or appears in a promo video, is at the core of Dieter Rams' 10 principles for good design.

Ive's inspiration on Rams' design principles goes beyond the philosophy and gets straight into a direct homage to real products created decades ago. Amazing pieces of industrial design that still today remain fresh, true classics that have survived the test of time.

The similarities between products from Braun and Apple are sometimes uncanny, others more subtle, but there's always a common root that provides the new Apple objects not only with a beautiful simplicity but also with a close familiarity.

1960s Braun Products Hold the Secrets to Apple’s Future

Braun Atelier TV and latest iMac 24.

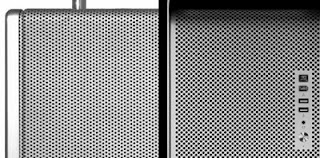

Braun T1000 radio and PowerMac G5/Mac Pro.

Detail of the radio perforated aluminum surface.

Braun T3 pocket radio and Apple iPod.

Braun L60 sound system and Apple iPod Hi-Fi.

link

Relating Products

I am going to collect a body of images of different fields of design that reflect the characteristics of Rams '10 principles of good design.' I intend to use them to illustrate the success of modernist ideas and how there still relevant today within design.

Existing Braun Products

link

Related Products

link

Images above sourced from 'Contemporary Design'- Catherine McDermott

link

link

link

Content Summary

From the research I have found I intent to explore the relationship between:

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

RESOLUTION CONSIDERATIONS - What is a publication? How is it made? What format could it be? How is the format relevant to the content? Is this important? What are the conventions of publication? How do you work with these? What are the rules? Do you have to obey them?

To get some ideas of how I want my publication to look I am going to start by researching Modernist graphic design to inform my design decisions; layout, colours, format.......

Relating Products

I am going to collect a body of images of different fields of design that reflect the characteristics of Rams '10 principles of good design.' I intend to use them to illustrate the success of modernist ideas and how there still relevant today within design.

Existing Braun Products

link

Related Products

link

Images above sourced from 'Contemporary Design'- Catherine McDermott

link

link

link

Content Summary

From the research I have found I intent to explore the relationship between:

- Modernism

- Bauhaus (Form follows function)

- Dieter Rams (10 principles of good design)

- Braun

- Apple

I intend to briefly touch on Modernism to give some context, compare the philosophy of the Bauhaus 'form follows function' with Dieter Rams '10 principles of good design ' to show how the initial ideologies derived from the Bauhaus have progressed and in my opinion, improved with time and technology to better suit societies needs within design. I will do this by comparing Rams designs for Braun with the contemporary, current designs of Apple, which are one of the most successful and iconic brands of the time. With doing this, I intend to communicate the success of Modernist philosophies by making the reader aware of there on-going presence within current design.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

RESOLUTION CONSIDERATIONS - What is a publication? How is it made? What format could it be? How is the format relevant to the content? Is this important? What are the conventions of publication? How do you work with these? What are the rules? Do you have to obey them?

To get some ideas of how I want my publication to look I am going to start by researching Modernist graphic design to inform my design decisions; layout, colours, format.......

For my publication grids are going to be a mandatory part of the design process and will help me layout the content clearly and efficiently.

I like the use of limited colour offset with the stock. It creates a clinical finish which is what I am wanting to achieve.

The use of geometric shapes would be relevant to the context and maybe a way of pagination?

From the examples I have looked at, I definitely think it a matt finish looks better, this is something to consider when I come to print.

To reflect the context I will use a sans-serif font.

I like the use of columns for the body copy, I will be using a grid system to layout the content so columns are something to think about.

This is a good use of negative space to create an interesting layout, type working alongside image.

From the research above this format seems to be a recurring theme within modernist publications. This is the format I will use for my publication because I think it relates to the content/context communicating modernism through a simple geometric form.

link

Finishing Techniques

These are the binding techniques that I feel are most relevant to the overall design and context that I am wanting to communicate.

Binding

Spiral, Plastic Comb and Wire-O

Finishing Techniques

These are the binding techniques that I feel are most relevant to the overall design and context that I am wanting to communicate.

Binding

Spiral, Plastic Comb and Wire-O

I like this method of binding because it relates to the ideas of modernism and truth to materials. It will also allow the pages to be opened flat.

Method: Creates a book by placing a strip, with one side adhesive, onto the spine and over the cover. Then the book is inserted spine side into a machine to heat the adhesive and add pressure to seal the edges.

This method is another possibility for my publication. Its unobtrusive, functional which relates to the 10 principles....

Saddle Stich

This method is really simple and cheap to produce but most importantly doesn't detract from the design.

No comments:

Post a Comment